POESIA E RIVOLUZIONE

curated by Leda Lunghi

Galleria Giampaolo Abbondio – Via Porro Lambertenghi, 6 – Milano

15 September – 30 October, 2021

Opening: 15 Sptember, h: 18.00

Poesia e Rivoluzione

di Leda Lunghi

Ho immaginato il cambiamento, la libertà, chiedendo a me stessa quanta forza essi contenessero, poi ho visto qualcosa in lontananza, impercettibile, ho udito un’eco lieve, il richiamo di un angelo, detentore della storia, portava con sé parole suadenti piene di forza, fascino e ardore; nel suo profondo una parte oscura, quell’angelo conduceva alla rivoluzione, mentre Clio, la Musa della storia osservava inerte senza testimoni.

La rivoluzione ha le ali della libertà, si schiude verso il cielo per poi diradarsi in tempi lontani, la si osserva sparire tra le nuvole. La rivoluzione è lo sbocciare della poesia, della passione e della lotta, è il desiderio fugace del cambiamento, dettato da ideali profondi, in cui si sviluppa la complessità umana, la rivoluzione è “ la lotta dell’uomo contro il potere è la lotta della memoria contro l’oblio. ” ¹

In questo vagare di memorie, di cambiamenti, di valori divenute melodie incessanti, unite da chimere trasformatesi poi in silenzi profondi, in questo cerchio perfetto di anime che danzano tra amore e odio, felicità smarrite tra passato e futuro, rimbomba il valore profondo del tempo, eterno, intimo, in cui l’angelo della storia, così chiamato da Walter Benjamin, cristallizzava i cocci di pensiero ², i dettagli delle nostre essenze e tra quei significati si possono ritrovare le origini, le motivazioni della nostra realtà più pura, quella in cui si rivela il nostro essere la nostra identità, i nostri destini, ciò che abbiamo di più prezioso e raro.

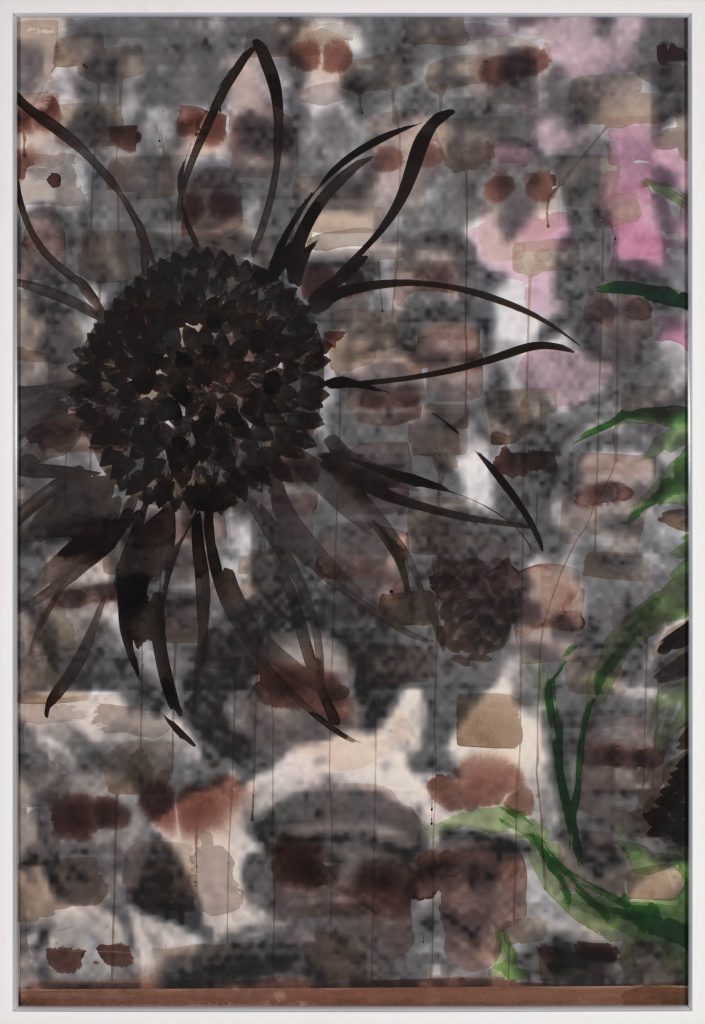

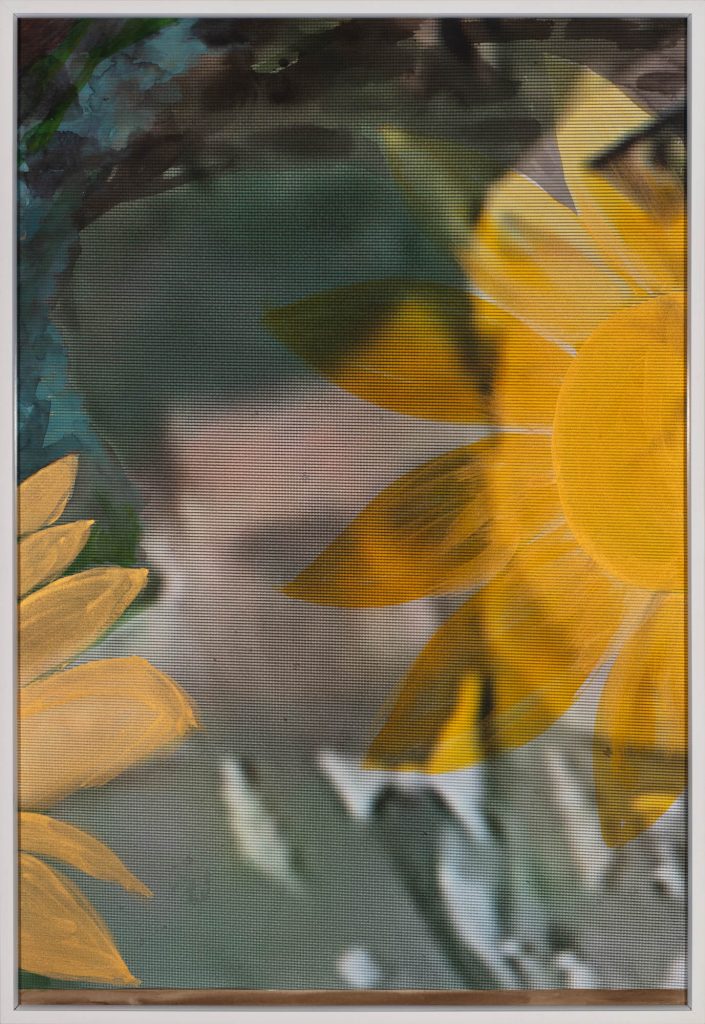

Lo spirito fresco della rivoluzione, il suo phatos è serbato nell’oblio, nel ricordo delle parole e delle immagini, esso corre sul filo di kairòs, il vento lo accompagna tra gli echi e le rovine, il logos lo conserva come un tesoro prezioso, abbandonato nelle profondità del mare. Per raggiungere quegli abissi e riportare le sue rarità in superficie abbiamo bisogno di parlarne, di rievocarle, di immaginarle. Le opere di Maria Magadalena Campos – Pons ci accompagnano in questo lungo viaggio. Nella poetica dell’artista cubana ritroviamo la sua essenza rivoluzionaria, delicata, malinconica, effimera; in quest’arte, cuore delle sue memorie ancestrali, emerge l’amore per la terra d’origine, Cuba: eccoli i suoi colori, i particolari che emergono dai lavori, rimandi a narrazione di storie e leggende. Osservandoli pare di udire un clamore lontano, voci di donne che tramandano antichi miti, rombi perduti di rivoluzioni fallite, riti religiosi, ed è quella terra che riemerge in quest’estetica, in un dedalo di odori, luci e simboli. Quella patria che sarà perennemente con lei, s’intreccia con l’attuale presente, là dove incontra la realtà, in una cerimonia di purificazione, di iniziazione, avviene il passaggio a questa duplice vita, in un’unione di verità storiche, in un’intima profondità di eclettismo. La spiritualità culturale rivelata da Maria Magdalena Campos – Pons, la suo condizione di esule, ci fa comprendere quanto rivoluzionario sia questo concetto e quanti artisti, percepiscano la necessita di raccontarlo, rispecchiandosi nelle proprie rappresentazioni mentali e immaginarie, trovando in esse una sorta di pace.

“In ultimo ci sarà un’immagine non una parola. Prima delle immagini le parole muoiono” ³, così parlava Cassandra tra le pagine di Christa Wolf nell’omonimo libro Cassandra.

La grande profetessa, morì in nome della verità, fu il suo coraggio e la sua presunta follia a portarla alla morte, nessuno accettava le sue troppo spesso scomode verità, ne evince che spesso il concetto di rivoluzione cela in sé tutt’altro che fortuna o serenità. Questo fenomeno trapela di solitudine, incomprensione, poiché colui (o colei) che lotta, si trova alienato e solo, in quanto il cambiamento è spesso un’utopia, un’idea dei folli, ed è a questi personaggi apparentemente fragili agli occhi della società, che Elena Bellantoni e Gianni Moretti dedicano le loro opere.

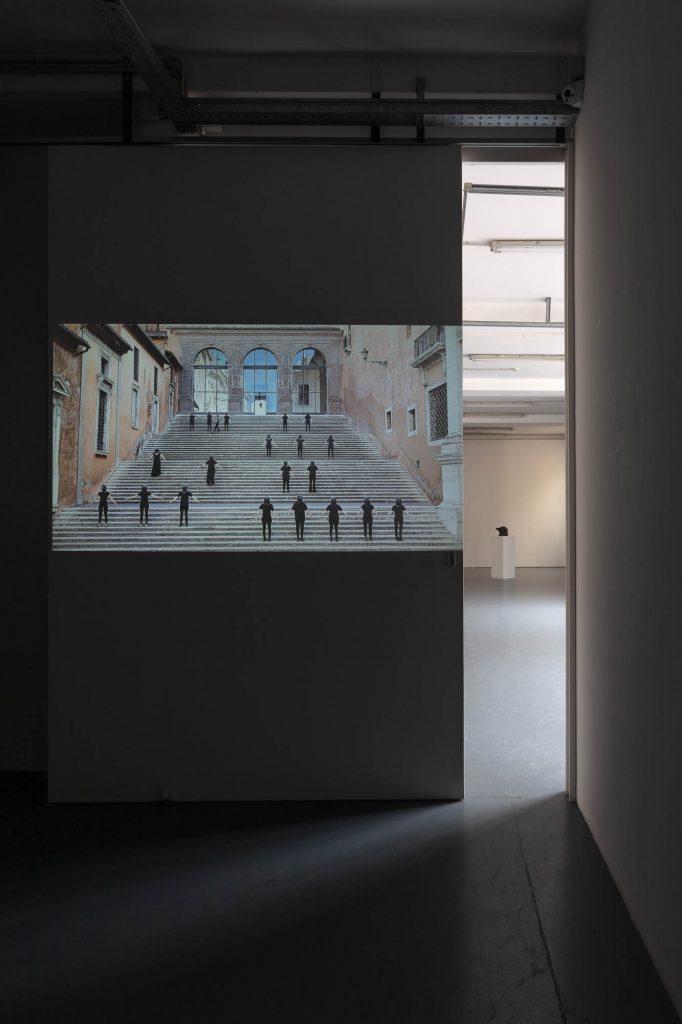

La prima, omaggia il grande registra russo Andrej Tarkovskij, reinterpretando il film Nostalghia. Girato in Italia, Gorčakov, il protagonista, è incapace di trovare un equilibrio, un’armonia con se stesso, si sente estraneo alla vita che gli scorre dinanzi, sopraffatto da un animo annebbiato tra malinconia e solitudine, deluso, trova rifugio nel riverbero della “pazzia” di Domenico, un poeta considerato “folle” dalle persone “normali” in quanto rimasto rinchiuso in casa per sette anni, nella convinzione di proteggere in questo stato di confinamento sé e la sua famiglia. Bellantoni con la descrizione di questo personaggio, tanto ossessivo e inquietante, quanto rivoluzionario e utopico, detentore di una verità ingenua, ma totalmente pura, rivelatrice dell’essenza radicata e primitiva della civiltà, accende un dibattito sul coraggio della fragilità e in contemporanea sul periodo storico appena conclusosi, il quale ci ha visti confinati forzatamente nelle nostre abitazioni.

In questa sorta di “fine del mondo”, come recitano per l’appunto le parole di Tarkovskij, nei mesi della pandemia, siamo divenuti spettatori di una rivoluzione umana, ci siamo sentiti protagonisti di una metamorfosi ovidiana, che ha coinvolto ogni tipo di essere vivente. L’artista sceglie di rappresentare quest’epoca storica con l’ambigua e mitologica figura del corvo, volatile misterioso, sacro quale la vita e la morte, il cui colore nero è segno dell’imperfezione del mondo.

Tutti dinanzi alla paura e alla morte siamo apparsi inermi e questo ci ha introdotto a una trasformazione. Il nostro DNA è mutato, ma non solo, ritrovatici dinanzi ad uno specchio, abbiamo visto oltre all’essere umano un intero mondo ramificato con tutte le sue fragilità, che si sono trasformate e si tramuteranno nel tempo in contaminazioni, cambiamenti ed emancipazioni. E’ su questo punto che si sofferma l’artista, sulla rivoluzione della fragilità, in questo gioco biunivoco in cui c’è chi cambia e c’è chi osserva.

Noi moltitudine di normali, bloccati, accecati e velati dall’indifferenza della nostra regolare consuetudine, osserviamo inerti la rivoluzione che Domenico conduce.

Paragonati agli ascoltatori del monologo estremamente lucido e rivoluzionario che il poeta tiene dal Campidoglio attraverso il quale decide di cambiare il mondo. Egli non solo parla della tragicità della situazione in cui la popolazione è afflitta, ma grazie alla propria convinzione spirituale si fa carico degli altri, arrivando al gesto estremo del martirio. Atto rivoluzionario, compiuto non solo attraverso l’importanza del logos ma anche mediante l’elemento fisico, che Bellantoni sottolinea ponendo in evidenza gli aspetti chiave della sua poetica: il linguaggio, la performance e il video. L’artista infatti interpreta il fuoco che brucia e divampa sul corpo, come l’ardere delle parole ed è con questo discorso poetico che ci riconduce alla forza rivoluzionaria dell’artista tout court, su cui grava l’immagine del preveggente e del premonitore.

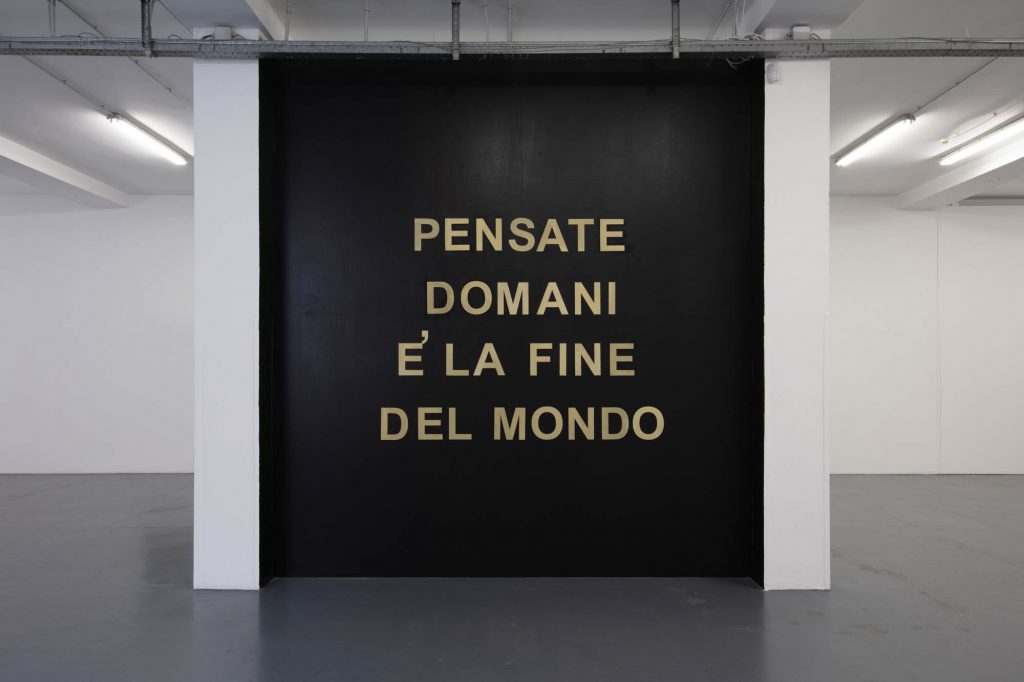

Aleggiano nel video le affermazioni di Domenico, in un racconto di realtà lirica e metaforica, in cui Bellantoni sviscera una molteplicità di significati e significanti; il segno del linguaggio è fermato per non essere disperso nel vento e inciso su preziose scritte di ottone tirate a lucido, adagiate come pelle di pellicola. Scritte che simboleggiano frammenti, quell’estetica del dettaglio da cui origina l’idea dell’artista, perché è sempre da una piccolo indizio, una traccia nascosta, una miccia apparentemente impercettibile da cui divampano le rivoluzioni. E’ un attimo, un’inquadratura lontana, un particolare, un cartello tra la folla: “Pensate! Domani è la

fine del mondo” , un monito, da cui questa ricercatrice di esistenze, prende spunto per l’omaggio alla poesia profonda e rivoluzionaria del regista e dei suoi valorosi anti-eroi.

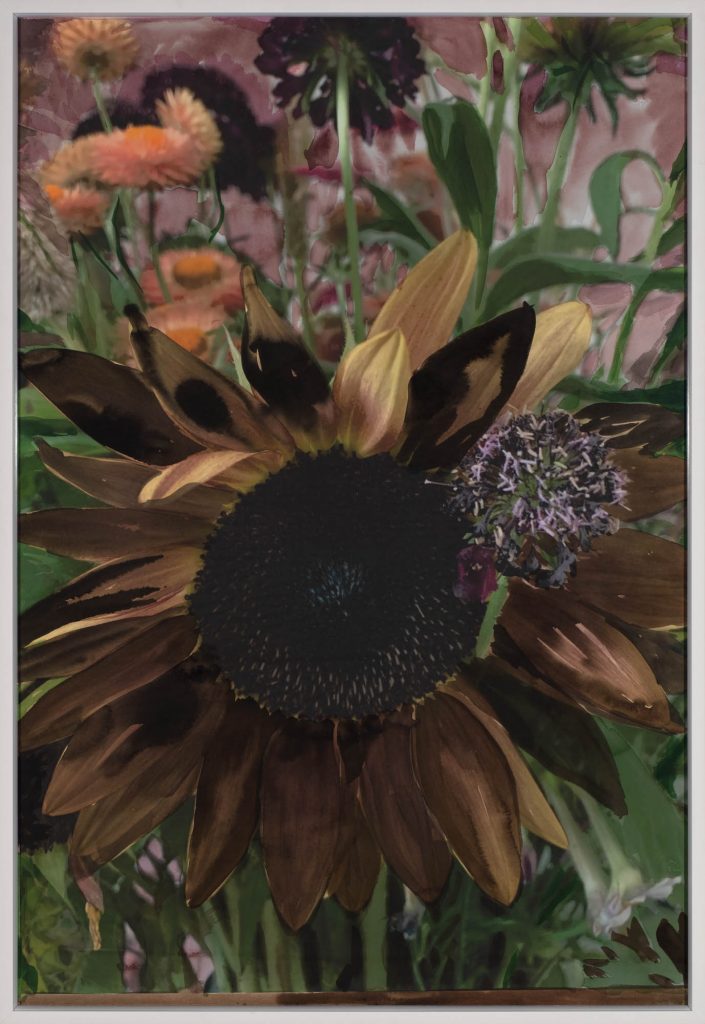

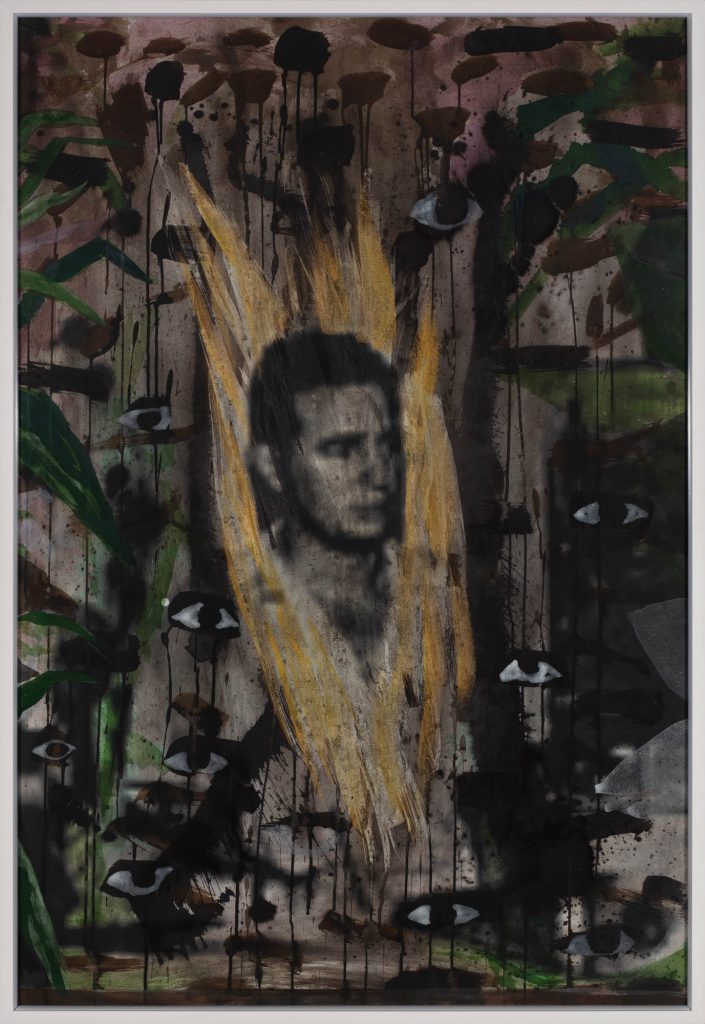

E’ in questo vagare di utopie, rivoluzioni dell’anima, del quotidiano che Gianni Moretti nelle sue opere, abbandonate, delicate, rarefatte, ci fa intravedere tra le ombre immagini vaghe e sfumate racconti di vite, nebbie di memorie, di coloro la cui rivoluzione è stata la capacità di opporsi alla società per sopravvivere, per affermare la propria notorietà nell’anonimato. La rivoluzione, quella di affrontare la vita e gli sguardi altrui nelle condizioni più avverse, possedendo il coraggio e la capacità di non cadere, per non divenire invisibili prima di tutto a loro stessi, per rimanere uniti a quel filo rosso che li integra al significato primo della vita, quello della libertà; illuminare queste vite, questi coni d’ombra è il centro di ogni rivoluzione.

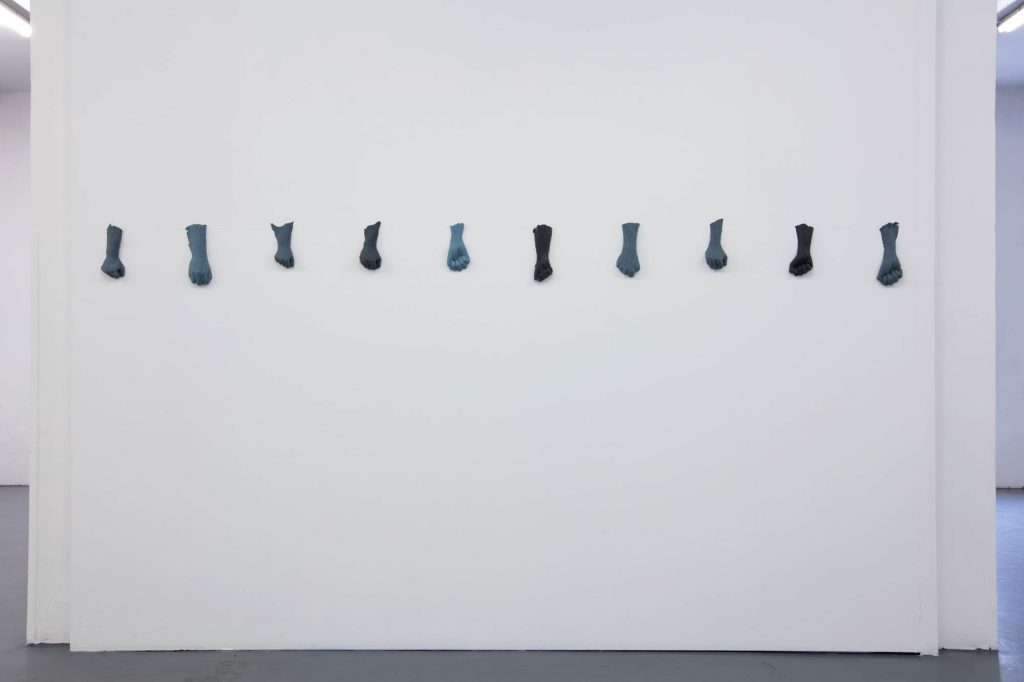

Un diritto negato, ecco cosa rappresenta nel lavoro Black powerless la giovane artista Binta Diaw un lavoro che rivela ideali, quelli che l’artista esprime profondamente e manifesta con furore in tutta la sua arte, cercando di portarci a riflettere e forse chissà a cambiare.

Figlia di seconda generazione, quei ragazzi nati e cresciuti in Italia, italiani in tutto e per tutto, ma che ricevono la cittadinanza solo a diciott’anni, ci racconta con questo lavoro, la generazione dello Ius soli, del diritto di cittadinanza.

Una generazione fantasma, abbandonata a se stessa, priva di tutele.

Con uno sguardo provocatorio, ma al contempo sensibile e poetico, Binta Diaw esplora questa problematica dal punto di vista politico, culturale, sociologico, ne evince un’opera corale, in cui l’artista prende il calco del pugno chiuso dei suoi coetanei afro-italiani, il simbolo iconico è quello che negli anni sessanta rappresentava l’ideale rivoluzionario delle Black Panther, non a caso segno dell’identificazione dell’orgoglio nero. Il suo potere nero viene posizionato al contrario, in nome dell’impotenza, un pugno che non detiene potere. Da qui il richiamo dell’artista a porre l’attenzione sui valori negati e il desiderio di eguaglianza per questa generazione, la sua sensibilità per la crescente alleanza demografica e corporea degli afro-discendenti italiani resi invisibili dalla nazione.

Il tempo scorre anche sul lavoro di Massimo Uberti dove antico e contemporaneo convivono nelle loro essenze più pure, attraverso la rappresentazione dell’oro e del neon, Uberti racconta la duplicità dell’arte, presente nella scritta : L’altro lato dell’arte.

Con queste parole, che magnetiche attraggono la nostra attenzione, con la loro libertà semantica ed estetica, egli descrive l’universalità dell’opera d’arte e in contemporanea il suo duplice significato di singolarità quale opera stessa, evocata ed elaborata dall’artista.

E’ l’antitesi, il duplice che troviamo in questo lavoro, ispirato dal titolo speculare della mostra ed è questa ambiguità perennemente presente nella sua poetica che si libera tra spazi di buio e luce, immensità misteriosa, ma contemporaneamente libera, audace, coraggiosa, con quello sfondo d’oro in cui riconosce, immaginandolo, un piccolo uscio, dove si perdono le linee minimali e geometriche delle parole.

Queste ultime esistono grazie ad un’ estetica raffinata e antica del nobile materiale aureo e dall’origine bizantina e successivamente medievale ed è in un gioco di equilibrismi antitetici, in cui notiamo come il pensiero scorre puro su questa poesia, in un sorreggersi di origini e attualità che si bilanciano perfettamente. Con quest’opera che tende verso l’infinito chiudiamo, con la preveggenza rivoluzionaria di ogni artista e con la loro indistinguibile capacità poetica di guardare oltre.

¹ Kundera M. Il libro del riso e dell’oblio p.14

² Arendt H. Benjamin W. L’ Angelo della storia p.105

³ Wolf C. Cassandra p.28

Poetry and Revolution

by Leda Lunghi

I envisioned the change, the freedom, asking myself how much power they contained, then I saw something in the distance, imperceptible, I heard a soft echo, an angel calling, a keeper of history, carrying silken words, full of strength, allure, and ardor, in its depths a darkness, that angel was leading towards the revolution, while Clio, the muse of history, observed motionless without testimonies.

The revolution has the wings of freedom, opening up towards the sky only to fade in distant times, one observes her disappearing among the clouds. The revolution is the blossoming of poetry, passion, and struggle, it is the fleeting desire for change, dictated by profound ideals, in which human complexity evolves, the revolution is “the struggle of man against power and the struggle of remembrance against oblivion.” ¹

In this wandering of memories, of changes, of values become endless melodies, bound together by chimeras transformed then into profound silences, within this perfect circle of souls that dance between love and hate, stray happiness between past and future, the profound value of time echoes, eternal, intimate, in which the angel of history, as Walter Benjamin called it, crystallized “the fragments of thought” ², the details of our essences and among those meanings one can find the origins, the motivations of our most undefiled reality, that in which our being and our identity, our destiny, are revealed, that which we hold most precious and rare.

The fresh spirit of the revolution, its pathos is guarded within oblivion, in the memory of words and images, it runs on the thread of kairos, the wind accompanies it among the echoes and the ruins, logos preserves it like a precious treasure, abandoned in the depths of the seas. To reach that abyss and retrieve that unwontedness we must speak of it, re-evoke it, imagine it. The works by Maria Magadalena Campos – Pons accompany us on this long voyage. In the poetics of this Cuban artist we discover her revolutionary, delicate, melancholy, ephemeral essence; in her art, the heart of her ancestral memories, her love for her land of origin, Cuba, issues forth; there are its colors, the details that emerge from her works, references to narratives of stories and legends. Observing them one seems to hear the distant din, voices of women that bequeath ancient myths, lost peals of failed revolutions, religious rites, and it is that land that re-emerges in this aesthetics, in a labyrinth of odors, lights, and symbols. That fatherland, which will be eternally with her, is intertwined with the present moment, there where it meets reality, in a ceremony of purification, initiation, is the passageway to this twofold life, in a union of historical truths, in an intimate profundity of eclecticism. The cultural spirituality revealed by Maria Magdalena Campos – Pons, her state of exile, makes us realize how revolutionary this concept is and how many artists feel the need to narrate it, seeing themselves reflected in their mental and imaginary representations, finding within them a kind of peace.

“In the end, there will be an image, not words. Words die before images.” ³ So Cassandra, whose name is the title of the book by Christa Wolf, speaks.

The great prophetess died in the name of liberty, it was her courage and presumed madness that led to her death, none who could accept her often uncomfortable truths, it follows oft that the concept of revolution conceals within itself anything save fortune or serenity. This phenomenon transpires solitude, incomprehension, since to struggle one, he or she, finds oneself alienated and alone, insofar as the change is often utopic, the dream of fools, and it is to these apparently frail individuals that Elena Bellantoni and Gianni Moretti dedicate their works. The first, an homage to Andrej Tarkovskij, reinterpreting the movie Nostalghia. Filmed in Italy, Gorčakov, the protagonist, is unable to find an equilibrium, a harmony within himself, he feels estranged from life that flows before him, overwhelmed by a spirit obscured between melancholy and solitude, disillusioned, he finds refuge in the resonance of Domenico’s “folly”, a poet by “normal” people deemed “mad” as he had shut himself in his house for seven years, convinced that in this state of confinement he was protecting himself and his family. Bellantoni, in describing this character, as obsessive and disquieting as he is revolutionary and utopian, possessor of a naive truth, though entirely pure, revealing a deeply rooted and primordial essence of civilization, sparking a debate on the courage of frailty and at the same time on the recently concluded historical period, which has seen us forcibly confined to our homes.

In this sort of “end of the world”, as in fact Tarkovskij’s words speak, in the months of the pandemic, we have become spectators of a human revolution, we have become protagonists of an Ovidian metamorphosis that has implicated all types of living beings. The artist chooses to represent this historical era with the ambiguous and mythological figure of the raven, a mysterious winged creature, sacred as life and death, whose black hue is a sign of the imperfection of the world.

Everyone before fear and death seemed helpless and this has brought us to a transformation. Our DNA has mutated but not only, finding ourselves before a mirror, we have seen beyond human beings and the entire world issuing in all its frailties, which were transformed and transmuted over time into contaminations, changes, and emancipations. And it is on this point that the artist dwells, on the revolution of frailty, in this bijective game in which some change and some observe.

We, multitude of normals, blocked, blinded, and veiled by the indifference of our customary habits, observe lifelessly the revolution that Domenico leads. Compared to the listeners of the extremely clear and revolutionary monologue that the poet gave at the Capitol with which he decided to change the world. He not only speaks of the tragic nature of the situation which afflicts the population, but thanks to the personal spiritual conviction he shoulders the burdens of others reaching the ultimate gesture of martyrdom. A revolutionary act, undertaken not only through the importance of the logos but also by way of the physical element, which Bellantoni emphasizes by highlighting the key aspects of his poetics: language, performance, and video. The artist in fact interprets the fire that burns and ravages the body, like the flames of words and it is with this poetic discourse that he leads us back to the revolutionary force of the artist tout court, which bears upon the image of the prescient and the prophetic.

In the video, Domenico’s words hover in a tale of lyrical and metaphorical reality, in which Bellantoni delves into a multiplicity of meanings and signifiers; the sign of the language is held down so as not to be dispersed by the wind and is engraved in precious phrases of brass polished and set like hides of filmstrips. Writings that symbolize fragments, that aesthetic of details from which the idea of the artist originates, because it is always from a small clue, a hidden trace, an apparently imperceptible wick from which revolutions flare up. It is but an instant, framed from a distance, a detail, a sign held in a crowd “Think! Tomorrow is the end of the world.” A warning, from which this researcher of existences takes her cue for the homage to profound and revolutionary poetry of the director and his valiant anti-heroes.

And it is in this rambling of utopias, revolutions of the soul, of the quotidian, that Gianni Moretti, in his abandoned, delicate, and rarefied, works, lets us glimpse among the shadows hazy and nuanced images,stories of life, mists of memories, of those whose revolution was the power to oppose society in order to survive, to affirm one’s reputation in anonymity. The revolution, of facing life and the gaze of others under the most adverse conditions, possessing the courage and the ability to keep from falling, to not become invisible first of all to themselves, to remain bound to that red thread that integrates them to the primary meaning of life, that of liberty, illuminating these lives, these cones of obscurity which is the center of all revolutions.

A denied right, that is what is represented by the work Black Powerless by the young artist Binta Diaw. A work that reveals ideals, those that the artist profoundly expresses and manifests with fury in all her art, trying to make us reflect and perhaps change.

Daughter of a second generation, those youngsters born and raised in Italy, Italian in all respects, but who obtain their citizenship only when eighteen, she tells us through her work, of the generation of ius soli, the right to citizenship. A phantom generation, left to themselves, deprived of protection.

With a provocative look, but yet sensitive and poetic, Binta Diaw explores this problematic from a political, cultural, sociological point of view. Thus follows a choral work, in which the artist takes the cast of the closed fist of her Afro-Italian peers, the iconic symbol was that which in the sixties represented the revolutionary ideals of the Black Panthers, not coincidentally a symbol of the identification of black pride. Its black power is placed upside down, in the name of impotence, a fist without power. From this, the call by the artist to observe the denied values and the desire for equality of this generation. Her sensitivity to the growing demographic and corporeal alliance of the Italian Afro-descendants rendered invisible by the nation.

Time also flows over the work of Massimo Uberti, where the ancient and the contemporary coexist in their purest essences, through the representation of gold and neon, and with this, he tells the duplicity of art, found in the phrase: “The other side of art.”

With these magnetic words that call our attention with their semantic and aesthetic freedom, he describes the twofold meaning of the work of art, its universality, and, at the same time, its uniqueness as a work in itself, evoked and elaborated by the artist.

It is the antithesis, the dual we find in this work, inspired by the specular title of the exhibition and it is this perennial ambiguity present in his poetics that frees itself in the spaces between light and darkness, mysterious immensity, but yet at the same time, bold, brave, with that gold backdrop in which one detects, imagining, a tiny threshold where the minimal and geometric lines of the words are lost. They exist thanks to a refined and ancient aesthetic of the noble aureus material and from the Byzantine origin then Medieval and it is in this game of antithetical balancing acts in which we note how thought flows pure along this poem, in a holding onto origins and relevance they are perfectly balanced. With this work that tends towards the infinite, we come to a close, with the revolutionary foreknowledge of every artist and their indiscernible poetic ability to see beyond.

¹ Kundera M. Il libro del riso e dell’oblio p.14

² Arendt H. Benjamin W. L’ Angelo della storia p.105

³ Wolf C. Cassandra p.28

–

POESIA E RIVOLUZIONE

Milano, Galleria Giampaolo Abbondio (via Porro Lambertenghi 6)

15 settembre – 30 ottobre 2021

Orari: martedì-sabato, 11-19

Ingresso libero

L’accesso in galleria seguirà le disposizioni vigenti in riferimento all’esibizione della certificazione Green Pass.

Informazioni:

Galleria Giampaolo Abbondio

Tel. +39 347 543 2014| www.giampaoloabbondio.com | info@giampaoloabbondio.com

Facebook: @galleriagiampaoloabbondio

Instagram: @galleriagiampaoloabbondio

Ufficio stampa

CLP Relazioni Pubbliche

Stefania Rusconi | tel. 02 36 755 700 | stefania.rusconi@clp1968.it | clp1968.it

Ph. Antonio Maniscalco